About 10 % of the male population and 3 % of females have colour issues that impact on their lives.

‘Colour blind’ is an emotional term, more correctly the word is deuteranope.

Complete colour blindness is very rare, more often we have a complex colour response that is not ‘colour normal’.

What colours might the deuteranope eyes of a painter be able to generate?

Quite a few of the greatest masters of painting, as in my case too, had unusual colour vision.

The authoritative Francis Pratt of the Painting School of Montmiral with whose assistance and mentoring I conducted numerous colour experiments calls it ‘special eyes’, having naturally a sense of colour vision many painters strive all their lives to attain.

They, we, learned to use this to create what appear to ‘colour normal’ people, delightful colour surprises.

On this subject in May 1996 Francis Pratt of the renowned Painting School of Montmiral kindly wrote for my web site:

“A surprisingly large proportion of the more celebrated Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and early Modernist painters were short-sighted.

This meant that when they were making paintings of landscapes they could see what they were painting clearly but what they were looking at was blurred.

Renoir and Cézanne are known to have seen this as an advantage.

Albrecht Dürer had one lazy eye.

This helped him with drawing from observation because using two eyes makes it more difficult to look at relationships between objects and their context.

Presbyopia (i.e. long-sightedness due to age) may have helped in producing much-appreciated stylistic developments of the later years of certain artists, including Titian and Rembrandt.

The visual capacities of both Monet and Degas degenerated in their later years with positive effect for future generations.

The former’s cataracts acted as red filters and explain the astonishingly red paintings he made towards the end of his life, which many forward-looking young artists found particularly exciting.

Degas suffered from a progressive failure of the colour receptors in the central part (the fovea) of the light-capturing receptor mosaic at the back of his eyes (the retina) leaving him more and more dependent on the colour-creating potential of the rod receptors in the periphery.

From around 1886, to compensate for the growing difficulty of seeing clearly, he started to double the size of his paintings.

Progressively his mark-making became looser and his colours brighter.

Moreover, since the rod receptors, which he was now forced to use, absorb light of a different wavelength to the cone receptors which dominate normal colour vision, his later paintings contain a choice of colours that strike modern eyes as unusual and exciting”.

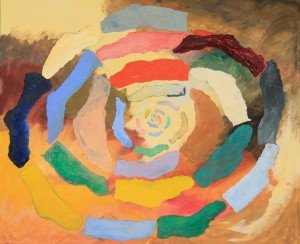

Painted by Gordon Frickers ‘Odd Socks’ measures 121 x 121 cms (48″ x 48″), oils, available, £3,000.

Thus, one way and another, here we have a particularly challenging painting, a great addition to any collection and ‘after dinner’ subject.